An article on the BSI website explains the rationale for the changes as follows:

“This revision of BS5250 comes at a time when buildings are under increasing stress from moisture for two complementary reasons:

- The effects of climate change will impact directly on buildings because of increased penetration of driving rain, more frequent, deeper and longer lasting flooding and increased atmospheric humidity that slows drying rates.

- Energy conservation measures to combat climate change include reduction in ventilation, which increases internal humidity, and increased levels of thermal insulation, which makes the outer layers of the fabric colder. Energy saving retrofit of traditional buildings, which have been in equilibrium with the ambient climate for many years, can lead to significant moisture problems in the structure.”

So, what are the fundamental changes, and how do they impact designers and contractors?

From condensation control to managing moisture

The new standard recognises the impact of moisture from both an internal perspective (condensation) and external (driving rain and increased atmospheric humidity).

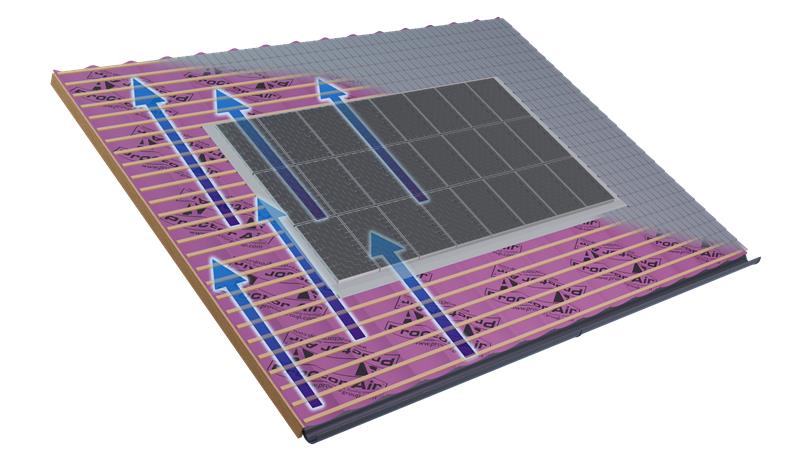

This change recognises a clear need to manage the balance of Heat, Air and Moisture movement throughout the building’s life cycle from design, construction, completion and use. Some companies already stress the importance of these factors under the principles of HAMM (Heat Air Moisture Movement), which emphasises the management of heat, air and moisture.

One example of this is where the design considers the effect of the insulation type and placement along with the vapour permeability of the various layers. This approach leads to a better balance of the key factors that produce a healthy building envelope that protects the occupants.

In addition to assessing energy performance, it is essential to determine how the building design balances moisture. BS5250 specifies the conditions when the simplified Glaser modelling is inappropriate and when more sophisticated modelling to BS EN 15026 is needed. The use of WUFI® software, which is fully compatible with BS EN 15026, dynamically predicts moisture movement and storage and condensation for each location.

Balancing these principles will involve calculations to assess condensation and moisture risks. Glaser calculations can do this but can have limitations, which a WUFI analysis can help overcome, e.g., rain and drying out of residual moisture in the construction. A WUFI calculation can show what effect differing performing VCLs can have on the structure and whether they are critical. A VCL should be used to reduce the moisture risks to acceptable levels but not be the sole protection method.

New Section on design principles for wall

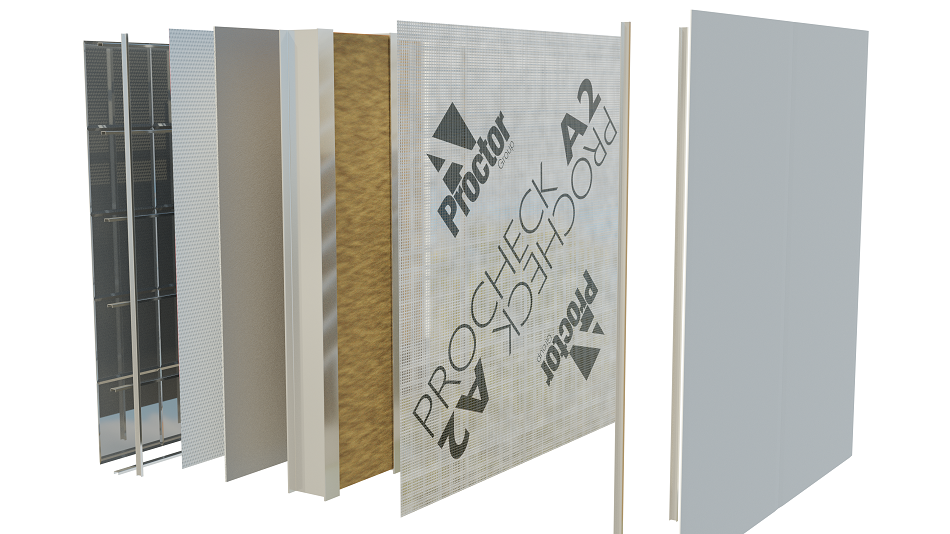

Section 11 of the revised standard provides new guidance on “Application of design principles – Walls.” This new section covers different categories of walls, from solid walls to framed walls, cladding systems (rainscreen cladding), SIPS, CLT, and Modular & Offsite.

In combination with the improved modelling analysis provided by WUFI, innovative new product developments in membrane technology offer high-performance solutions to meet these guidelines for walls.

Solid walls: One example particularly suited to solid walls is Procheck® Adapt. This variable permeability intelligent vapour control layer adapts its vapour resistance to suit the environment, becoming vapour tight in the winter and vapour open in the summer. So, the membrane adapts to changes in humidity levels and allows the structure to dry out in the summer and sunny days in spring and autumn while protecting it from moisture overload in the winter and cold, wet days.

Refurbishment: With an increasing requirement to refurbish and upgrade the design of existing buildings to meet the challenges of climate change, space-critical solutions that offer superior thermal performance, waterproofing and breathability are fundamental to achieving the requirements within the new regulations.

The recently upgraded and refurbished Grade II* listed Balfron Tower project in Poplar, East London, provides an example of a solution of managing the moisture in a highly sensitive refurbishment whilst working within space-critical conditions.

Alisan Dockerty, project architect at Egret West, explains: “The existing wall construction of the Grade II* listed buildings meant that space for traditional insulation was limited in some instances. Therefore, we chose to apply Spacetherm® A rated Aerogel Blanket from the A. Proctor Group, a high-performance insulation blanket with A2 fire rating, capable of achieving the BRE’s surface condensation analysis target temperatures of 16°C, whilst providing us with a minimum loss of space.”

Spacetherm A rated is a flexible, high-performance, silica aerogel-based insulation material of limited combustibility suitable for use in exterior and interior applications. The product optimises both the thermal performance and fire properties of façade systems, enhancing the thermal performance of the ventilated façade and addressing thermal bridging in the façade.

Cladding systems: Managing the moisture within cladding systems have traditionally focused on combining the insulation with a vapour control layer (VCL). However, a VCL becomes less critical when the insulation is positioned externally than insulation solely applied between the framing behind the sheathing board. The introduction of externally applied self-adhered vapour permeable yet airtight membranes offer a solution to this.

VCLs (particularly variable resistance membranes) can be advantageous in some applications to reduce the moisture flow through a building envelope but are less critical in other areas, depending on the insulation placement. For example, when insulation is placed between the frame of a timber frame building, the moisture risk may be too high to omit the VCL. Consequently, a VCL would help to reduce vapour progressing through the structural frame. However, balance this with insulation placed externally to the structural frame, and the dew point potential is reduced due to the warm frame. Therefore, the VCL becomes less critical yet still good practice.

Managing the gap between “As-Designed, As-Built and In-Service”

Another fundamental addition to the revised BS5250 standard is the inclusion of guidance on ADT (“as designed, theoretical”) and ABIS (“as-built and in service”). In addressing this, the standard notes the following:

“In both new and existing buildings, the gap between design and as built is now clearly understood. There are very few buildings without “in service” effects of residual moisture from construction, moisture generated in usual use or, where more serious, moisture due to building faults. The following three conditions occur:

- as designed on the drawing board;

- as built in practice; and

- in service after several years of occupancy.

The assessment of moisture risk in buildings or building elements varies according to these different conditions, requiring a different approach according to the type of building and the quality of work.”

The revision of BS5250 seeks to address the challenge of managing the moisture risk by recognising the different conditions that apply to each project. It is clear from the changes made to the standard that there is a need to manage the balance of Heat, Air, Moisture movement (HAMM) throughout the building’s life cycle. Understanding the importance of these vital elements upon the building envelope is crucial to successful construction and operation.

Request a Sample

Technical Advice

CAD Detail Review

U-Value Calculation

Book a CPD

Specification Check