The problem with “destructive” internal insulation

In 2020, Níall specified an internal insulation solution for a building conversion project. Inside the 600mm sandstone walls, he detailed a 50mm clear cavity, then a timber stud frame with PIR insulation fitted between the studs.

Originally, he intended the insulation to be applied directly to the face of the wall, but the Building Standards Officer requested the cavity in accordance with the Technical Handbooks (Scotland’s equivalent to the Approved Documents used in England and Wales).

Two years later, delayed by the Covid pandemic, the project was on site. Níall filmed a YouTube short – which has now been viewed over 200,000 times – showing the insulation solution in place. The video wasn’t a comment on the type of insulation, but on the thickness of the build-up required and how it meant none of the building’s original features could be retained.

Due to this loss of character, Níall characterised the method as “destructive.”

The type of insulation matters more than its thickness

In early 2025, Níall created a full YouTube video called ‘How to insulate a solid wall in the UK.’ He looked at issues like how thick solid wall insulation should be, and what best practice is for insulating old buildings internally. In the video, he referenced his original Short and admitted that, were he to do the project again, he would not insulate the walls the same way.

What matters most is not the thickness of the insulation, but the type of insulation and the method of construction, he recognised.

That’s because knowledge and understanding around solid wall insulation had changed a lot since 2020, when he first specified the project. In 2021, for example, the UK Government published

‘Retrofit Internal Wall Insulation – Guide to Best Practice.’

The guide documents how traditional solid walls don’t rely on drying to the outside only. Sun and wind are an important part of helping wet walls to dry, but traditional internal finishes, like lath and plaster, are also ‘breathable.’ That is, they allow the passage of moisture vapour, meaning walls can also dry to the inside when required.

Fitting ‘non-breathable’ (i.e., vapour closed) insulation materials to the internal face of a solid wall inhibits the wall’s ability to dry to the inside. The face of the wall is colder and potentially damp, increasing the risk of mould and eventual decay. While that might not happen on every building, there’s no way to be sure of what is going on behind an insulation system.

Taking the lowest risk approach

There are a host of different ways that internal solid wall insulation can be approached, influenced by factors like how the original wall is constructed. There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach – but there is a starting point that should be common to all projects.

The retrofit best practice guide states, quite plainly: “For internal wall insulation, often the lowest risk approach is to use a moisture open design.”

A moisture open, or vapour open, specification ensures that moisture transport can occur through the complete wall build-up, reducing any risk due to damp or saturated walls.

There is, however, one significant drawback. A vapour open insulation solution is usually thicker, because vapour open insulation is not as thermally efficient as the rigid PIR boards that Níall specified in 2020.

He carried out U-value calculations to compare a mineral wool solution to his original design, and it would have required an extra 80mm of insulation. That would have meant an internal insulation build-up that took around 250mm (10 inches) off the floor space of the room in which it was installed.

Learning more about aerogel

Many subscribers who watched the video left comments about an insulation material that Níall had heard of but was not familiar with: aerogel. It led him to investigate further and create a follow-up video called ‘The thinnest insulation in the UK.’

If you need to insulate solid walls internally and maintain a vapour open construction, but you don’t want to lose valuable floor space or remove historic features like cornices, is aerogel the answer?

In the course of putting the video together, Níall spoke to Proctor Group about the Spacetherm® range of aerogel products. It led to Proctor Group sponsoring the video and, subsequently, Níall’s whole channel.

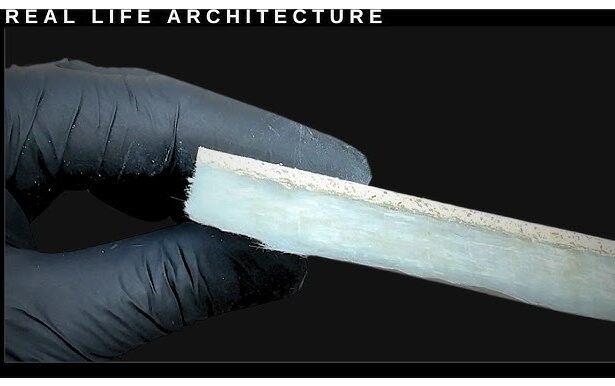

Aerogel is made by taking silica gel and freeze drying it until the liquid component has dried out and been replaced with gas. The result is a lightweight material with a host of beneficial properties: low thermal conductivity, hydrophobic, and vapour open.

“This material is extremely resistant to heat transfer and its properties as an insulation material are almost supernatural,” said Níall, referencing a NASA photo in which a flower is protected from the flame of a blowtorch by nothing more than a thin layer of aerogel.

However, the rigid material is also extremely brittle. To Níall, it wasn’t obvious how it could be used in construction – until the Proctor Group technical team told him more about Spacetherm.

The Spacetherm range from Proctor Group

To create a more usable aerogel product, the silica aerogel is embedded into a carrier fleece, such as polyester or glass fibre. This makes it more flexible without compromising the integrity of the material or its excellent thermal properties.

In his video, Níall focused on the version of the product where the aerogel fleece is bonded to magnesium oxide (MgO) boards of various thicknesses. The product is also available as a blanket, which has been used in applications as diverse as boats, pipes under bridges, and vans converted to motorhomes.

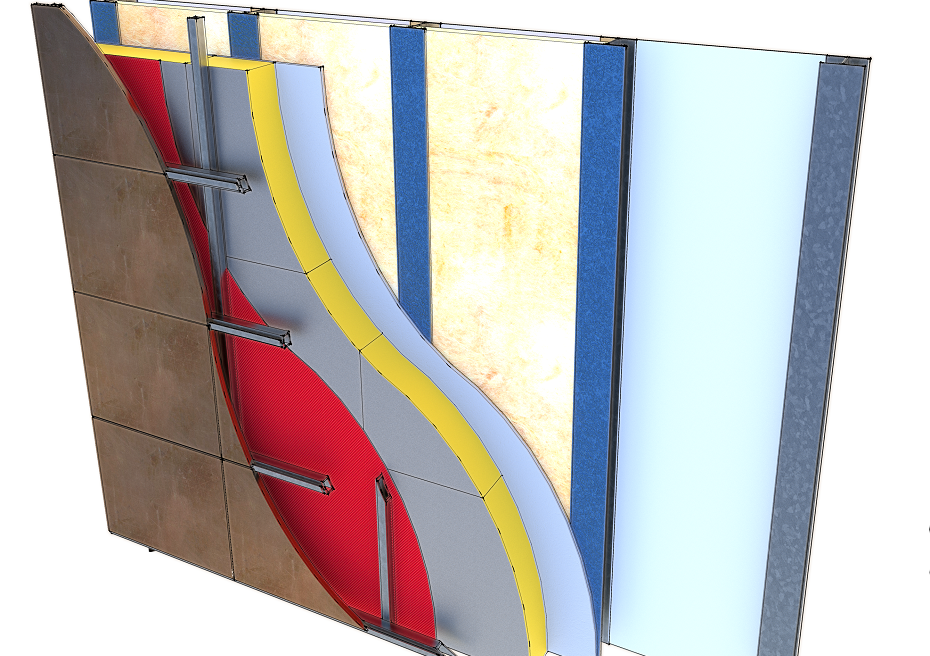

As aerogel is hydrophobic, it does not absorb liquid water from wet walls. But its vapour openness allows moisture vapour to pass through, maintaining the breathability of the traditional wall construction. This combination of properties means a Spacetherm product can be installed directly to the face of a wall, without a clear cavity needing to be maintained.

Saving space with Spacetherm

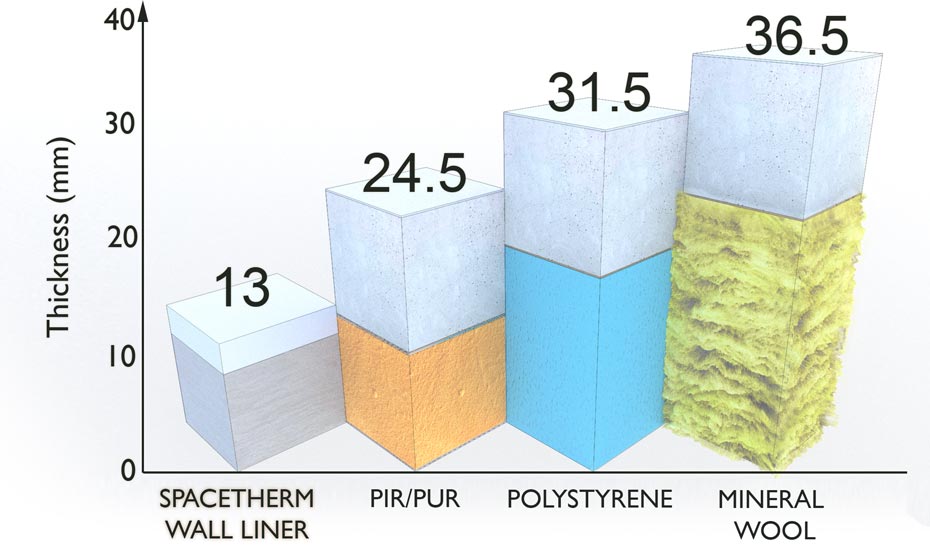

On top of not needing an air cavity, Spacetherm also has the lowest thermal conductivity of any insulation material offered for internal wall insulation. This makes it an ideal space saving solution for existing buildings.

A typical U-value for a 450mm uninsulated solid wall is around 1.5 W/m2K. Applying 16mm Spacetherm (10mm insulation plus 6mm plasterboard) directly to the wall can reduce that U-value to 0.72 W/m2K – halving the heat loss through the wall and potentially making a significant difference to thermal comfort.

This means you could strip the existing plaster from a wall (which is often around 25mm, or one inch, thick), apply the Spacetherm insulation, and have no impact on an existing cornice.

Níall ran a series of U-value calculations comparing Spacetherm to alternative PIR and mineral wool solutions that achieve a similar U-value. Both the PIR and mineral wool build-ups would need an air cavity, resulting in total thicknesses as follows.

- Spacetherm: 16mm

- PIR: 54mm (assuming 9mm plasterboard).

- Mineral wool: 71mm (assuming 9mm plasterboard).

This impressive performance does come at a cost, with Spacetherm being around £97 per square metre. That may preclude it from widespread use in a retrofit project. But where better thermal performance is required in space-critical areas, compared to the potential risks and long-term costs of using the wrong insulation or not insulating at all, the price is more than justifiable.

Getting serious about solid walls

An increased focus on making existing buildings more energy efficient is requiring many designers and specifiers to learn about traditional building techniques for the first time.

“I was never taught this,” said Níall, “because the focus was always on new buildings. But solid walls were the norm until 100 years ago, so this type of work is only going to get more common.”

However, knowledge on the subject is “patchy, and sometimes contradictory.” And as the recent publication date of the retrofit best practice guide shows, we are only just starting to formally capture that knowledge.

“Many of us are having to relearn old concepts, as well as learning new ones like airtightness,” concluded Níall. “That is only becoming more complex as we move towards Passivhaus, or EnerPHit levels of performance for existing buildings.”

It has led to Níall incorporating his learning into his architectural practice, as well as seeking to share it with others through his YouTube channel so that others may benefit from it too – an approach that Proctor Group wholeheartedly supports.

Find out more about Spacetherm insulation solutions offered by Proctor Group, and see more of Níall’s videos on his YouTube channel, Real Life Architecture.

Request a Sample

Technical Advice

CAD Detail Review

U-Value Calculation

Book a CPD

Specification Check